Field Notes: Building Outpost - A Text-Based Survival Game

2024-09-15

·

⏱︎ 14 min read·

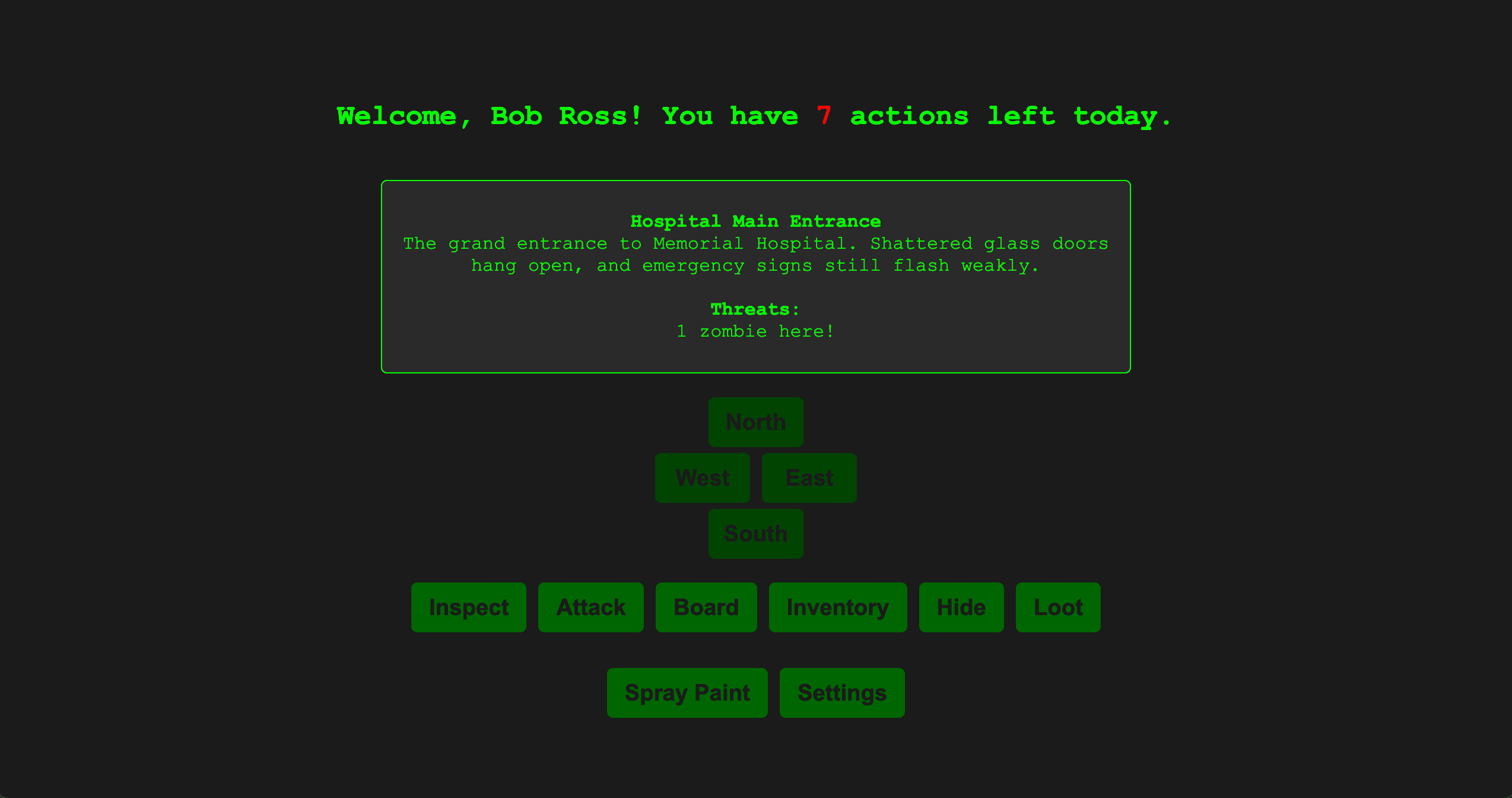

The Beginning: Just an Idea and a Green Terminal

When I was younger, I played a game much like this. You could build a character and get plopped down anywhere on the map, be given a few actions each day, and you had to carve out your own path. I never particuarly liked videogames where I had to sit down and devote an endless number of hours to a storyline, instead, I could chip away a little bit each day and still very much participate in the multiplayer.

It seemed like a simple enough concept for me to learn about how auth works, databases, deploying an application, multiplayer features, while not worrying about intense graphics or much in the way of design. The concept was simple, a terminal-like interface and limited actions.

V1: Making Something Move

The first version was embarrassingly basic:

- A green-on-black terminal interface

- A few arrowed buttons to move around

- A text display that said where you were

- Zero persistence (refresh = restart)

function moveNorth() {

currentPosition.y += 1;

updateDisplay();

}

But seeing it start to come alive was exciting enough for me to try and get a little more sophisticated.

Adding the Map: Grid by Grid

Next came the actual game world. I started with a basic grid system:

const map = {

dimensions: { width: 24, height: 24 },

currentPosition: { x: 15, y: 15 }

};

This is where Claude became invaluable. I knew I wanted a hospital complex to staty, but needed help thinking through everything first:

- How big should the map be? If it's too big, you need an innumerable number of people for it to be fun. And even then, who is going to play my stupid game for long enough to find out?

- What types of buildings are even in a small city / town?

- How do you make each location unique?

Claude helped me map out a 24x24 grid, with a 5x5 core hospital building and surrounding areas, each with its own purpose and potential for storytelling. They had to follow some sort of logical flow as well (e.g. the parking lot couldn't be right next to the patients rooms.)

Location, Location, Location

With the grid in place, I added basic location data:

const locations = [

{

x: 15,

y: 15,

name: "Hospital Main Entrance",

description: "Glass doors hang open, emergency signs still flashing weakly."

}

// ... and so on

];

It wasn't as simple as an undertaking as I thought. When I had initially started with a 100x100 grid, I realized just how many descriptions I needed to write and get into the system. So not only did Claude help with that, it also helped me in realizing a 24x24 was much more relevant (as it was still a load of locations) and also how to apply a logical flow to some of the map. At some point, I'll need to properly map it in Figma and rethink the city from the ground up, but good enough to start!

The Great Database Effort

This is where things got interesting (and complicated). I needed to move from static data to a living world. Enter Supabase. Without this, nothing the user did would ever persist. They wouldn't have a user account, so we'd never be able to store their unique decisions. Furthermore, even if they had an account, we still needed a way to store their decisions at all!

First Database Attempt: The Learning Experience

My first database structure was... let's say optimistic:

CREATE TABLE players (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY,

position_x INTEGER,

position_y INTEGER

);

I was messing around in the UI of Supabase and trying to manually build out the database. That's when I realized that I could ask Cursor exactly what database schema I needed, and it wrote me SQL to run in order to design the database.

Learned pretty quickly that I needed way more than that. The second version added, although much more to come:

-- Track player state

CREATE TABLE player_state (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY REFERENCES players(id),

health INTEGER,

actions_remaining INTEGER,

last_action_refresh TIMESTAMP

);

-- Track world state

CREATE TABLE location_state (

x INTEGER,

y INTEGER,

current_items TEXT[],

zombie_count INTEGER,

PRIMARY KEY (x, y)

);

At this point, it was that much easier to write SQL for what I needed past that point. Illustratively, if I wanted to wipe out all the users from the database, clear the graffiti, add zombies - you name it!

The "Real-Time" Challenge

The biggest challenge wasn't storing the data - it was keeping everything in sync. Every player movement needed to:

- Update their position

- Check for other zombies nearby

- Load location state

- Calculate available actions

Naturally, it wasn't ever going to be as intense as another video game. Even having said that, at this juncture, it's going to be hardly real-time. All I'll do at this point is run these checks after each player takes an action (e.g. moves, attacks, reloads), but at some-point I would love for the health to dynamically update as actions are taken against a player.

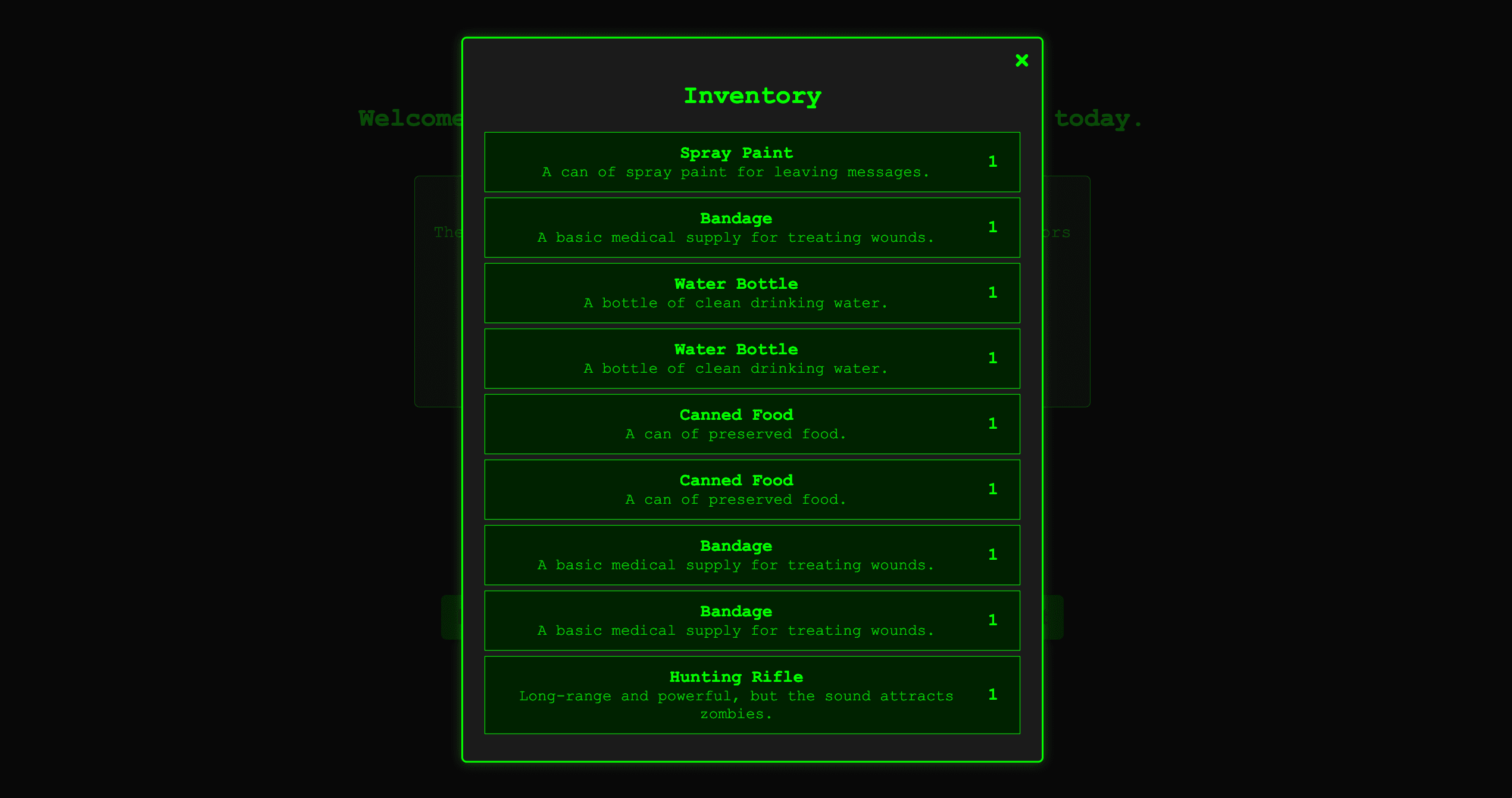

The Inventory Puzzle

Inventory management required its own database evolution. We needed to not only create the inventory items, but we needed to allow the player to see them, to use them, to have default inventory. Furthermore, we needed some items to also open action sets, e.g. spray when holding graffiti. Other items might be informational, or useless until future development.

Above all that, I also needed to add the modal to open the inventory, for it to check against the player in the database, and update accordingly.

Authentication: Making It Secure

When I started building Outpost, I thought authentication would be the easy part. "Just add a login button," I told myself. "How hard could it be?"

Narrator: It was harder than I thought.

The First Attempt

I started with Supabase because everyone kept saying how simple it was. The basic setup looked straightforward enough.

It worked great... until it didn't. Users would be logged in, then suddenly logged out. Sometimes they'd stay logged in but couldn't access their data. I started learning about things I'd never considered:

- Sessions: Just because someone logged in once doesn't mean they stay logged in forever

- Tokens: These little keys that prove you are who you say you are (and they expire!)

- State Management: Keeping track of whether someone is actually logged in across the whole app

The Breakthrough

After a lot of trial and error (and many console.log statements), I finally understood what I needed.

export async function getPostBySlug(directory: string, slug: string): Promise<Post | null> {

try {

let fullPath = path.join(directory, `${slug}.mdx`)

if (!fs.existsSync(fullPath)) {

fullPath = path.join(directory, `${slug}.md`)

}

const fileContents = fs.readFileSync(fullPath, 'utf8')

const { data, content } = matter(fileContents)

return {

slug,

title: data.title,

date: data.date,

content: content.trim(),

tags: data.tags || []

}

} catch {

return null

}

}

I'm still not 100% sure I've caught all the edge cases, but at least now I understand why authentication is more than just a login button. There were all sorts of important implications around settings, how many tries a user gets, storing information. It's about keeping users secure and their data protected, even if it means spending way more time than you initially planned.

Is it perfect? Probably not. But it works, and more importantly, I understand why it works. And sometimes that's enough for v1.

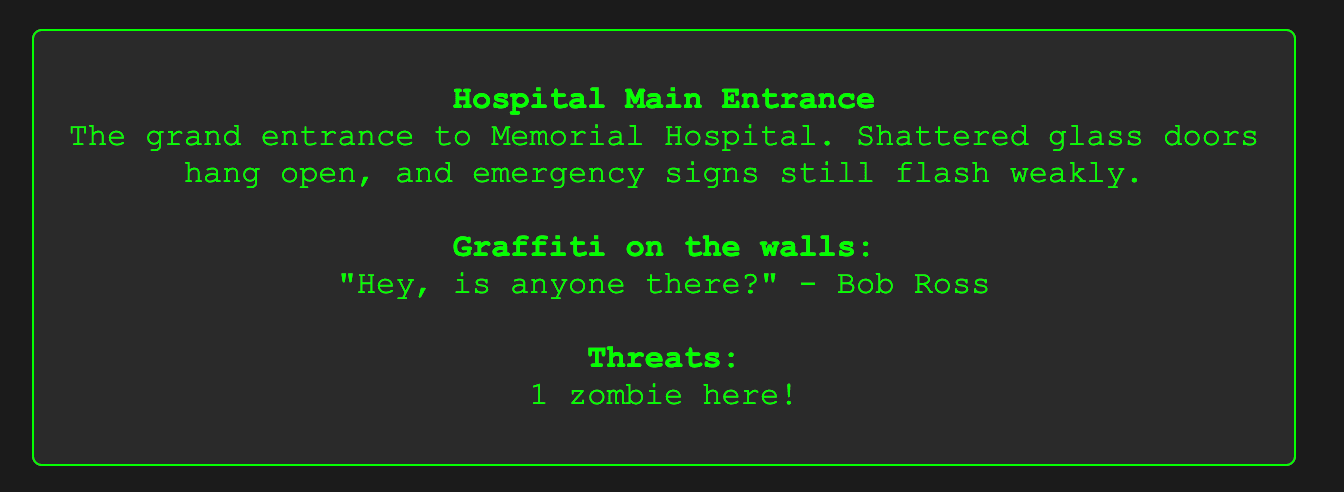

Final Touches: Graffiti and Atmosphere

With the core systems working, I could add the fun stuff:

- Player-left messages (graffiti system)

- Detailed location descriptions

- Environmental storytelling

The graffiti system needed its own table:

CREATE TABLE graffiti (

id UUID PRIMARY KEY DEFAULT uuid_generate_v4(),

location_x INTEGER,

location_y INTEGER,

message TEXT,

player_id UUID REFERENCES players(id),

created_at TIMESTAMP DEFAULT now()

);

This system, as stupid as it is, is something I always found really fun. Of course, it invites a really dark side of the internet to participate, but the idea of being lost in a game, leaving a message, and thinking someone might find it seemed so....fun.

Lessons Learned

Of course, this game is far from finished. And I'll continue updating this log as I push it farther along into something that I share more holistically. Even then, I'm in a large way hacking this together - so production ready might never be a thing for this project. Having said that, the whole intention is to learn principles and have a fun project to make the process easier.

Start Simple, Really Simple

- Getting basic movement working was more valuable than planning the perfect database structure – If you can have a basic UI and core functionality, plugging a database in is not as bad as you'd think

Database Design Is Never Done

- Every new feature meant revisiting and often restructuring tables

- It was useful for me to create handy SQL queries to use for testing purposes (like resetting the database)

Real-Time Is Hard

- Managing state across multiple clients takes careful planning

- My implementation is a very simple idea of "real-time", more realistically, everything happens on load / action. So this would be an area I would love to greatly improve down the road, otherwise we're going to likely run into weird inconsistency / timing issues.

Auth Is Never Simple

- Plan for all the edge cases

- Session management is crucial